The Magnetic North – filmmaker’s childhood dreams of Eskimos

When I was eight, I was introduced to the north by films screened in our classroom. Most of the films were from the National Film Board of Canada, a big factory building that sat not far from where we lived in Montreal. Many of the films shown were boring expositions on agriculture, or other such topics, and I would put my head down and catch up on my sleep - in the pitch black mornings of winter, I was out early before school on my paper route, delivering the Gazette. But it was the films about Eskimos that woke me up in class. I could relate to them the next day as I trudged through the mountains of snow with my large bag of newspapers. My imagination would run free and in no time I was using Eskimo techniques. I got the idea of using a Komatik to haul my papers – I had to take the place of the dogs after unsuccessful attempts at harnessing the sled to the family poodle.

It was around this time in the early 'sixties that our family visited the Canadian Guild of Crafts – the first organization to exhibit and sell Eskimo art in southern Canada - now called Inuit art, but more on that later. On this day several large wooden crates had just arrived from Port Harrison and Cape Dorset and wonderful carvings emerged from the white straw packing. When they were laid out on the long wooden tables I was hooked. You were allowed to handle the soft soapstone pieces and I was told if you rubbed them the grey stone would blacken. I bought two small carvings - a bird for twenty-five cents and a seal for thirty-five cents. If you lined them up they would appear to kiss. I spent hours rubbing them. It was my first physical contact with the north as I held these carvings and imagined the artist who had also handled them.

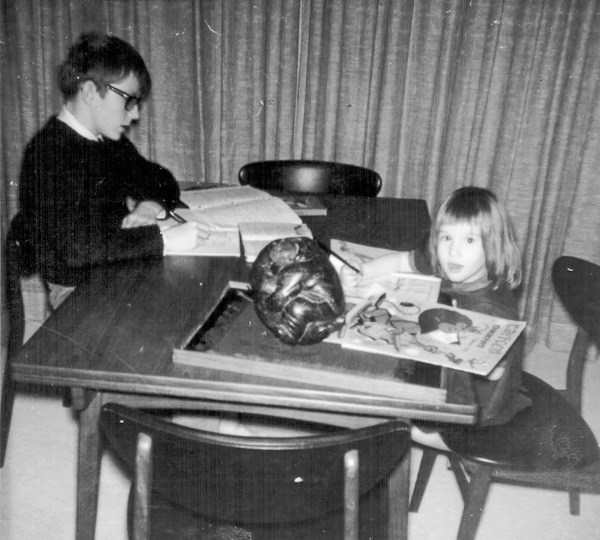

My father brought home a beautiful black carving that day. It was about seven inches tall and about the same diameter, with a heavy weight and almost sphere-like shape. It's a carving of an Inuk and a polar bear. It's like a snapshot of a man and bear as they meet in an embrace - the way you would hug a long lost friend. There was so much movement in the piece - it looked like the man would topple over on top of the bear - like in the next frame of a movie. As if he was making love to the bear. On closer inspection you could see that the man had a knife in his hand and so you knew this was not a dance of friendship - it was a dance of survival. Who would win this embrace you did not know.

The carving sat in the middle of our dinner table all the years I was growing up, and I would stare at it every night as I ate my supper – wondering what the artist had in mind. It was a great conversation piece. My grandmother seemed a bit confused and wondered why a carving of a bear eating a man alive was on the dinner table. She too would stare at it uncomfortably between courses. I think it made me like it even more - it was disturbing, inconclusive, still alive and threatening day after day - always a mystery. My thoughts about it changed over the years and I still look at it with wonder.

These works of art instilled in me a curiosity of the mystery and spirit of the north and its people. And so I jumped at the first opportunity to go north.

Director’s Journey in 1968

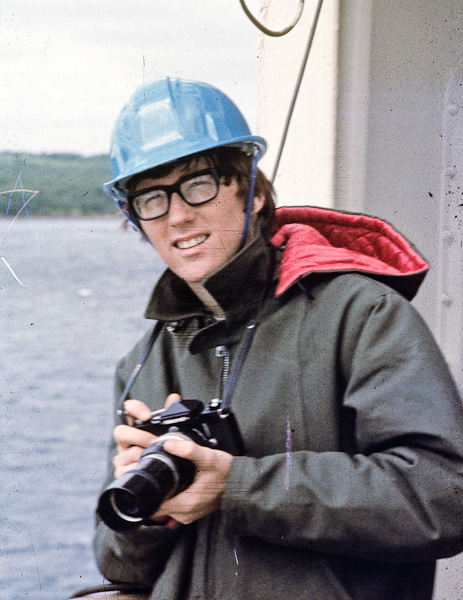

At sixteen, with my 35mm camera in hand, I boarded a supply ship in Montreal bound for Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island, the farthest northern port in the High Arctic. It was a summer job and all I had to do was help unload the hundreds of oil drums we had on board. The mystical force of the land and sea as we moved north took me by surprise.

The first signs of the north were the great icebergs we were trying to avoid. Then it was the whales, the seals and the walrus that I had seen interpreted as carvings on those gallery tables. As we glided into Lancaster Sound the captain told us we were entering the fabled Northwest Passage. Within a few days we were immobilized by the ice, like Sir John Franklin and the other sailors before him, who perished in the 19th century in these same waters. There we sat in silence with only the eerie sounds of the ice creaking against the steel hull below. After what seemed like an eternity, waiting for an icebreaker to clear our path, we finally set foot on land, in this vast and seemingly empty space.

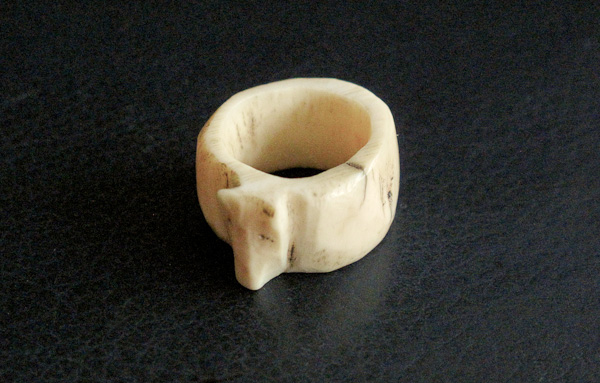

Empty, that is, until little dots of colour appeared on the horizon, and before I knew it surrounding me were smiling and laughing children, with bright knitted hats. One of them, without my knowing, placed a carved bone ring in my pocket. I discovered it when I reached in for another roll of film for my camera. When I asked, no one would say who put it there. I persisted and finally several kids pointed to a shy little red-faced boy of about seven. I will never forget his smiling eyes. I took his photograph to freeze that moment in time. It was my first entry point into his culture. He wanted nothing in return for his gift. He was not looking for acknowledgement or payment. It was just a selfless act of friendship on a seemingly barren land.

The kids led me to the village on the shore. I was carrying soapstone that I had acquired from the ship and wanted to give some to any carvers who might be around. I was working there for several weeks and spent my off hours in the village talking mainly in sign language to the local carvers and hanging around with the kids. I had the usual 'sixties crop of hair and the women thought I was pretty funny and giggled as I walked by. At least I assumed it was the hair they thought funny.

The contact I made with the Inuit gave me a fresh cultural and historical sense of my country that was deeply felt. This was 1968, just one year after Expo67 with its theme of "Man and His World" and I had seen "Eskimos" with their drums performing at the Canadian Pavilion.

Thoughts of what it meant to be Canadian were very much in the air in those turbulent days in Montreal with the terror of FLQ bombs blasting out a message of Quebec nationalism and the idea of creating an independent nation. Floating into this world of an ancient oral culture allowed me to contemplate time and think about space - Canada. The experience provided me with elements that were missing in my civilization to the south - a mystical connection to the land and an infinite sense of time. For several months I had escaped television, newspapers, radio, telephones and replaced it with a contemplation of time (ancient oral culture) and space (landscape). I found a kind of equilibrium within this experience. The shift from consuming media to feeling my presence on the earth as a human being grounded me spiritually and culturally to this place and it remained with me for the rest of my life.

My grandmother, a teacher, had instilled in me a sense of history, but in the north Inuit history seemed timeless – a continuum of oral culture that had existed here for countless years. To experience a culture that had survived on this land and sea since before the time of Christ was astounding to me. We had just celebrated Canada's 100th birthday. And with the intensity and emotion that only a teenager can feel, I came back to my family and friends in the south and told them they must, before they die, see the north and its people.

Journey to Nunavut in 2012 to make “Arctic Defenders”

It was many years after my enlightening journey north as a teenager that I learned a horrible truth about the history of the Inuit I had visited in Resolute Bay. Just eleven years before my visit, our government had transplanted them to populate the High Arctic, in the name of Canada's sovereignty. The Inuit in Resolute Bay had been moved over two thousand kilometers north from their home in Inukjuak (Port Harrison), Quebec, on the shores of Hudson Bay. They were dropped off by ship and left to fend for themselves without any supplies or shelter from the government. They had never before experienced such cold and twenty-four hour winter darkness.

Separated from their families, this act can be compared to Stalin's practice of shipping dissidents to the Gulag. It was part of Canada's strategy to claim sovereignty in the High Arctic. When I asked John Amagoalik, one of the radical Inuit leaders, who tells his story in our film, if he was bitter about the experience he simply said "no, I'm disappointed, I wish they had told us the truth. Inuit would have probably gone up and worked with the government, better prepared with proper essentials, but they chose to lie to us".

What I didn't realize at the time, as I was steaming north on a ship in 1968 to see the Eskimos of my childhood dreams, was that a group of radical Eskimos were envisioning a political movement. One of their first acts was to protest the use of the word Eskimo. This was not a word they used in their language. They called themselves Inuit. With our last film "Passage" I got to know Tagak Curley who played a profound role in the film and he told me the story of how he and others like John had accomplished this incredible political transformation with land claims and the creation of the Nunavut government. With all the media hype about Canadian sovereignty in the north we thought it was the right time, for us in the south, to hear what the Inuit have to say about their political culture and the meaning of sovereignty.

I am very privileged to be making this film with the radical "Defenders" of Nunavut and with Oo Aqpik, a young Inuk woman I met at a screening of "Passage" in Ottawa. In the 1990's, she was an observer of the political process and the creation of Nunavut when she was just sixteen. We travelled north to research the film over a period of two years. This is the story of the "Arctic Defenders" – the ones willing to dream and to fight for the survival of an independent and unique culture within Canada.

John Walker, March 20, 2013

Photo Gallery

Photographs © John Walker