The Environment

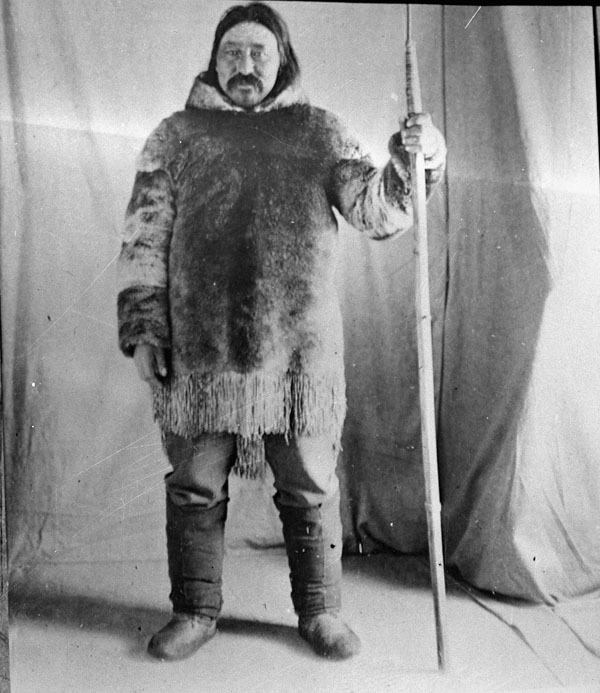

Canada’s arctic environment has been the preeminent factor that has shaped the development and the cultural life of the Inuit people. Northern isolation has influenced the political and economic development of the Inuit, while the wildlife of the region has been a determining factor in their overall well-being, both historically and up to the present day. The natural resources of both land and sea, including the hunt for caribou, muskox, polar bears, seals and whales have contributed to a traditionally nomadic lifestyle, where the Inuit have been subject to seasonal changes and migrations. Dependent on these patterns, the Inuit have formed a strong reliance on, and connection to, the environment. They have learned to live harmoniously, adapt when necessary, and have accumulated extensive knowledge of their environment based on centuries’ worth of collected observations.

Prior to the 1920s, the people of the Baffin region were mostly isolated in their contact with the federal government of Canada. The first federal intervention to manage northern resources occurred in 1921 with the creation of the Northwest Territories Branch of the Department of the Interior. While one of the primary administrative functions of the office was to manage the development of natural resources, including mining interests, the branch also introduced a series of new regulations, including game quotas that restricted access to traditional Inuit hunting grounds.

Throughout the 1950s the focus on the affairs of the Northern people and their environment intensified. In this period, the first government relocation programs took place in the Eastern Arctic. In 1953 Resolute became a town with a permanent human settlement. Prior to this, the area had typically only been visited during annual hunting trips. The families that eventually settled in Resolute at the suggestion of the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources did so in part for the availability of wildlife. The families of the new settlement were mostly dependent on caribou and seals that were readily found in the area around Barrow Strait. Seal meat provided the most important source of protein, while their skins were important for clothing and trade.

In addition to government relocation programs, federal management of the arctic also became a matter of strategic importance. An airbase was constructed at Resolute in 1949, and this was quickly followed by the construction of sections of The Distant Early Warning Line or DEW Line in the Eastern Arctic beginning in 1954. The project had a dramatic impact on the environment of Resolute and throughout the Eastern arctic. As wage employment increased in Resolute, the traditional activities of hunting and trapping tended to become part-time rather than full-time endeavours for the men of the settlement.

In addition to government relocation programs, federal management of the arctic also became a matter of strategic importance. An airbase was constructed at Resolute in 1949, and this was quickly followed by the construction of sections of The Distant Early Warning Line or DEW Line in the Eastern Arctic beginning in 1954. The project had a dramatic impact on the environment of Resolute and throughout the Eastern arctic. As wage employment increased in Resolute, the traditional activities of hunting and trapping tended to become part-time rather than full-time endeavours for the men of the settlement.

By the early 1960s, the hunters of Resolute first began to notice a scarcity of caribou in their hunting grounds. Changes in the artic environment had not been uncommon. In Canada’s Relationship with Inuit: A History of Policy and Program Development, author Sarah Bonesteel notes that, “During the early and mid twentieth century, Inuit and non-Inuit harvesting of animal resources in the Arctic, including whale and caribou, contributed to severe animal de-population, and shortages of resources for Inuit use.” (Bonesteel, 112).

On-going shortages eventually led to greater intervention on the part of both the Canadian government and the Inuit people. Federal interventions included environmental impact assessments and legislation to manage Arctic wildlife and promote sustainability. Throughout the 1970s Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) was the primary agency responsible for northern resource management. The agency played a dual role, tasked with both protecting Inuit interests while also providing licensing for activities in northern development. In this period a number of important legislations and assessments aimed at safeguarding the arctic environment were enacted, these include: the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act (1970), the Oceans Dumping Control Act (1975) and the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry (1977). In 1973 the Federal Environmental Assessment and Review Process (EARP) was also created. This process scrutinized proposals for northern land and resource development through relevant federal agencies. Projects with the capacity to significantly impact renewable or non-renewable resources were further recommended to the Federal Environmental Assessment Review Office (FEARO) for additional review. Canada’s newest Federal assessment process, Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, was passed in 2012, and includes assessments of economic and social impacts as well as environmental.

Much of the legislation that was passed throughout the 1970s and 1980s was a direct result of a greater global awareness of environmental issues. In the 1970s the developed world pushed an agenda to identify and combat containments in both air and water. While the DEW Line contributed to some contamination, most arrived in the arctic from other more industrialized locations by way of air or water. These contaminants included compounds such as DDT and PCBs, toxins that found their way into resources frequently used by the Inuit, including polar bears, whales and fish. While there were successful efforts to ban these containments throughout the 1970s and 1980s, in many cases the toxins remained long after they were initially introduced (Bonesteel 115). As a result of these findings, the Northern Contaminants Program was established in 1991 by the Canadian government in an effort to promote awareness and reduce the level of contaminants (Bonesteel, 115)

Much of the legislation that was passed throughout the 1970s and 1980s was a direct result of a greater global awareness of environmental issues. In the 1970s the developed world pushed an agenda to identify and combat containments in both air and water. While the DEW Line contributed to some contamination, most arrived in the arctic from other more industrialized locations by way of air or water. These contaminants included compounds such as DDT and PCBs, toxins that found their way into resources frequently used by the Inuit, including polar bears, whales and fish. While there were successful efforts to ban these containments throughout the 1970s and 1980s, in many cases the toxins remained long after they were initially introduced (Bonesteel 115). As a result of these findings, the Northern Contaminants Program was established in 1991 by the Canadian government in an effort to promote awareness and reduce the level of contaminants (Bonesteel, 115)

As government intervention increased, so too did the political awareness of the Inuit. Concerns over dwindling resources led the Inuit community to organize to voice their concerns, and at times challenge federal authority. The Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) was founded in 1971 (formerly Inuit Tapirisat of Canada) as national advocacy group representing Inuit interests. In addition to speaking out on environmental issues, the group has also addressed political, social and cultural issues affecting the Inuit communities of Nunavut, northern Quebec and Labrador. In 1977 the Inuit Circumpolar Conference was held in Copenhagen, Denmark. This first meeting of the world’s Inuit ended in the creation of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), an international body representing the unified interests of the Inuit of Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Russia. Since its founding, the ICC has spoken out on issues of indigenous rights, and they have consulted on the formation of national and international policies intended to protect the arctic environment. Within Canada, since the increase in political awareness among the Inuit, and their subsequent mobilization beginning in the 1960s, the Inuit have achieved the settlement of several land claim agreements with the federal government. These agreements have increased the acres of protected lands devoted to national parks.

The negotiation of land agreements and the administration of national parks, has ultimately led to greater cooperation between the Inuit and the federal government. Management of renewable and non-renewable resources requires ordinances governing the control of traditional hunting grounds, wildlife protection, arctic tourism and the development of lands for a number of purposes including oil exploration and diamond mining. These activities have the potential to transform the Inuit way of life in ways both positive and negative. Tourism, mining and oil production, all offer significant opportunities for wage employment and provide revenue for the territory of Nunavut. But these activities all open up the lands to a degree that will potentially cause irrevocable change or damage. Tourism increases foot traffic in previously undisturbed areas, while developing new industries will increase pollution, cause potentially irreparable damage to land, and threaten local wildlife by disrupting migratory patterns or encroaching upon habitats.

More recently, the threat of global climate change is the primary environmental concern of the Inuit. Early on, the Inuit people recognized signs of global climatic shifts, including warmer overall temperatures as a result of shorter winters and lengthier summers. The impact of climate change on the Inuit has already been significant, making weather unpredictable and more dangerous to travel and effecting migratory patterns and hunting stocks of animals that have traditionally sustained the Inuit diet. In response to these changes the Inuit became early advocates for national and international policies addressing the issue of climate change. The ICC first addressed the issue in the 1980s, and since then have advocated for international action. Canada’s Inuit have contributed much to the national and international discussions on climate change, as well as the body of research that supports the findings of the scientific community. The traditional knowledge has provided valuable insights on long-term environmental patterns, cycles and changes that have since been linked to global warming and climate change. This knowledge has been increasingly valued and incorporated into scientific studies of climate change. Among the most important of these studies has been The Arctic Climate Impact Assessment published in 2004. This study documented some of the most compelling evidence of climate change in the arctic region including: “increased northern temperatures, rising sea levels, decreased extent of summer sea-ice, melting glaciers, coastal erosion, northern extension of the tree line ad reduced permafrost.” It was noted that these condition will have a dramatic affect on both arctic animals and the Inuit people.

More recently, the threat of global climate change is the primary environmental concern of the Inuit. Early on, the Inuit people recognized signs of global climatic shifts, including warmer overall temperatures as a result of shorter winters and lengthier summers. The impact of climate change on the Inuit has already been significant, making weather unpredictable and more dangerous to travel and effecting migratory patterns and hunting stocks of animals that have traditionally sustained the Inuit diet. In response to these changes the Inuit became early advocates for national and international policies addressing the issue of climate change. The ICC first addressed the issue in the 1980s, and since then have advocated for international action. Canada’s Inuit have contributed much to the national and international discussions on climate change, as well as the body of research that supports the findings of the scientific community. The traditional knowledge has provided valuable insights on long-term environmental patterns, cycles and changes that have since been linked to global warming and climate change. This knowledge has been increasingly valued and incorporated into scientific studies of climate change. Among the most important of these studies has been The Arctic Climate Impact Assessment published in 2004. This study documented some of the most compelling evidence of climate change in the arctic region including: “increased northern temperatures, rising sea levels, decreased extent of summer sea-ice, melting glaciers, coastal erosion, northern extension of the tree line ad reduced permafrost.” It was noted that these condition will have a dramatic affect on both arctic animals and the Inuit people.