The Arrival of Government and the Rise of Settlement Living

Prime Minister Louise St. Laurent stood before the House of Commons in December 1953, and declared:

“Canada has governed the NWT in an almost complete state of absentmindedness for ninety years.”

He was not exaggerating. A series of events had forced the Canadian government to revisit its northern policy, or lack thereof. The Cold War was escalating and Canada again realized that it must take action if not to protect its sovereignty then at least to assert it. At the same time the government was receiving harsh criticism in the newspapers as reports of starvation trickled south with returning military personnel and appeared in newspapers and popular books such as Farely Mowat’s The Desperate People. This newfound interest in the social conditions amongst Inuit was part of a larger Canadian social program that saw family allowance instituted in 1944.

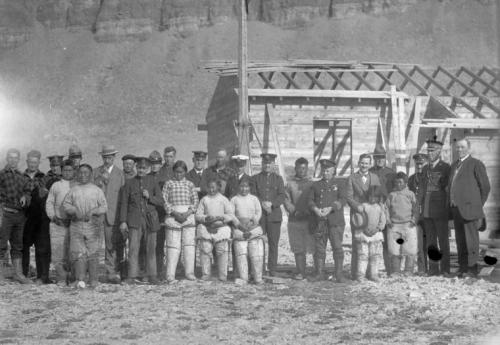

By 1953, there were no government programs in the north. The few mission schools in the Eastern Arctic had been set up by missionaries as had the hospital in Pangnirtung. The HBC and RCMP provided relief where they were able, and offered basic medical treatment. That year, the Department of Natural Resources was reorganized and given the name the Department of Resource and Development became the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources. Two northern service officers were appointed with the responsibility of coordinating the work of the RCMP, HBC and missionaries to help improve the economic and social living conditions of Inuit. What followed was an increasing government presence in the north that would have dramatic effects on Inuit way of life.

In an article published in the 1953 edition of the Beaver, Jean Lessage, the Minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources wrote that the object of government policy was to:

Give the Eskimos the same rights, privileges, opportunities, and responsibilities as all other Canadians; in short, to enable them to share fully the national life of Canada. It is pointless to consider whether the Eskimo was happier before the white man came, for the white man has come and time cannot be reversed. The only realistic approach is to accept the fact that the Eskimo will be brought ever more under the influences of civilization to the south. The task, then, is to help him adjust his life and his thoughts to all that the encroachment of this new life must mean.

He went on to outline what would become the Department’s policy toward Inuit. In his view, the Canadian life and that of the Inuit were both changing and that they must come under the same governing influences in the realm of economics, law, education, religion, employment, community and national life.

Economics

With the collapse of the fox-fur market in the 1940s, Inuit were left without a reliable method to earn an income to supplement their harvesting. In the 1950s, the Federal Government attempted to address the northern “economic crisis”.

R. Quinn Duffy, tells us that the government adopted a dual approach. In those more remote areas, where Inuit still pursued hunting activities the government “was to leave their life as undisturbed as possible.” However, the government would begin transferring Inuit from their traditional lands to areas that the government considered more productive. These relocations occurred throughout the Eastern Arctic, and often with little input or communication between those making the plans that the relocatees.

R. Quinn Duffy, tells us that the government adopted a dual approach. In those more remote areas, where Inuit still pursued hunting activities the government “was to leave their life as undisturbed as possible.” However, the government would begin transferring Inuit from their traditional lands to areas that the government considered more productive. These relocations occurred throughout the Eastern Arctic, and often with little input or communication between those making the plans that the relocatees.

In areas were permanent contact had been established, Inuit would receive training and support to enter into the white economy. Government workers were sent north, first as NSOs and later as Area Administrators, to develop economic programs that would see Inuit become less reliant on the traditional hunting and trapping activities. One of the more successful of these initiatives was the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, which produced artwork revered around the world. Inuit also found opportunities to work in construction as part of the expanding military presence and housing requirements of the Eastern Arctic. They also worked as guides and support personnel for the natural resource industry.

Most of the worked done buy Inuit were in the unskilled trades, while southerners with training were transported north to fulfill the more technical and better paying positions. While these types of employment provided an alternative to the income they lost without trapping it also contributed to the centralization of Inuit in settlements.

Education

Education became another priority of the government. An education system based on southern models was imposed on Inuit. This form of education stood in stark contrast to their traditional methods of learning that Inuit had relied upon for centuries to transmit knowledge. Inuit education valued observation while the southern model was based on rote learning. The curriculum was equally foreign; books containing reference to thanksgiving turkey, farming and office buildings held no cultural relevance. The language of instruction for all classes was English, because none of the teachers could speak Inuktitut.

Although earlier attempts had been made to provide for camp schools, by the mid 1950s, schools were begin built in the settlements along with small hostels to house Inuit students whose parents were encouraged to continue their traditional semi-nomadic hunting lifestyle. Many Inuit have reported that they were threatened with the loss of family allowance if they did not send their children to live in the settlements to attend school. Most parents refused to part from their children and moved into the settlements. The settlements, rarely situated at good hunting grounds offered little opportunity for Inuit to continue on their seasonal rounds thus further increasing their reliance on the wage economy and government support.

Throughout the 1960s programs were put in place to develop Inuit specific curriculum and address other inadequacies of the education program. This included teacher-training programs, employing Inuit teaching assistants, offering financial assistance for higher education and vocational training. Despite this progress, education remained an assimilative process, and would remain so until Inuit governance developed and fought for a more appropriate model.

Health Care

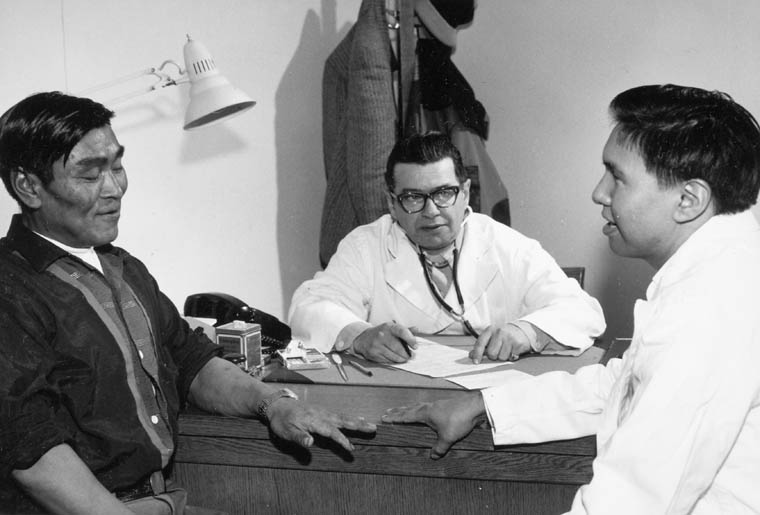

The 1940s saw a high rate of infant mortality and rampant respiratory disease amongst Inuit. Many Inuit were sent down south to be treated in southern sanatoria for tuberculosis and other diseases. The Qikiqtani Truth Commission found that “Medical strategies intended to improve Inuit health by removing patients to southern hospitals succeeded in their primary goal but inflicted lasting damage on many individuals and their families.”

The staffing of military installations in the north, and the construction of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line required large numbers of southern personal. Trained medical personnel were present at most military installations and provided health care services to Inuit living around the base or station. As the Inuit population rose, healthcare workers struggled to treat the requests from Inuit. The government began crating nursing centres in the most settlements while the only hospital was located at Frobisher Bay (now Iqaluit).

As health services improved and better housing became available, the rate of infant mortality and respiratory disease declined. Settlement living, however, posed new health care problems. Inuit diets shifted from ones made up of health country food to one of packaged and processed goods available in northern stores. This combined with a relatively sedentary lifestyle led to a rise in heart disease, obesity, and diabetes. Substance abuse and domestic violence also became significant health concerns that Inuit communities would begin coping with.

Housing

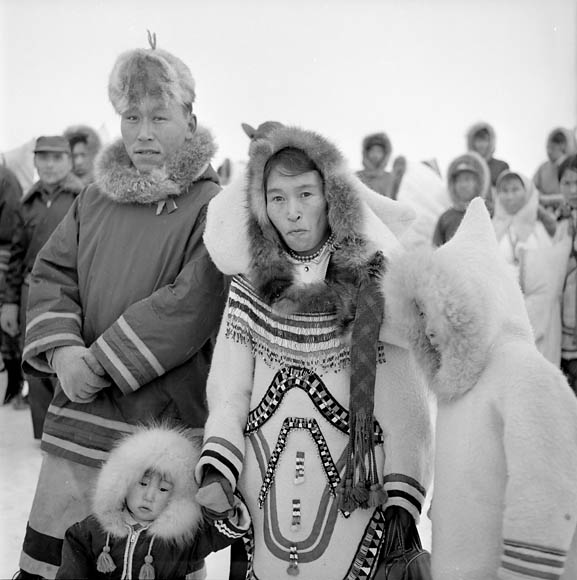

Closely tied to healthcare was the provision of the government’s housing policy. Up until the 1940s, Inuit lived in skin tents, snow houses and other portable type dwellings that suited their travelling lifestyle. The government linked the sanitation conditions of these dwellings with a rise in communicable diseases. This combined with the difficulties the government faced in delivering health and social services led the government to develop a housing program that saw houses erected in the settlements.

The first southern type houses erected in the Arctic were developed for the growing number of southerners who were living in the north delivering education, health and administrative services. The first attempts at Inuit houses, including a Styrofoam igloo, had ceased by the 1960s. The government introduced several programs to help Inuit finance their home purchase, including Eskimo Rental Housing Program.

By the early 1970s, the transformation from a semi-nomadic hunting society to a settlement based society was complete. But it was in these settlements that the beginnings of Inuit political development could be traced. From the time that Inuit arrived in the settlements they actively participated in organizations that helped govern the community. AS time progressed they took on larger roles.